The Great Migration and the Doom Cycle

History can help us see the present, the future, and ourselves if we let it

Thanks for being a subscriber to Let's Not Be Trash. If you’re new here, we (Mostly me, Evan J. MastronardiandKarina Maria write about patriarchy, politics, race, culture, music, and ruminations. The goal is to talk about important issues, in a way that is digestible and relatable because nobody wants to read a Ted Talk.

It’s the holiday season, so if you haven’t already, consider becoming a paid subscriber. If you want to support me financially but don’t want to commit monthly, buy me a coffee, or a PS5, whatever is cheaper.

If you like my substack and want to discover other great writers, check out this directory from Marc Typo called The Cook-Out.

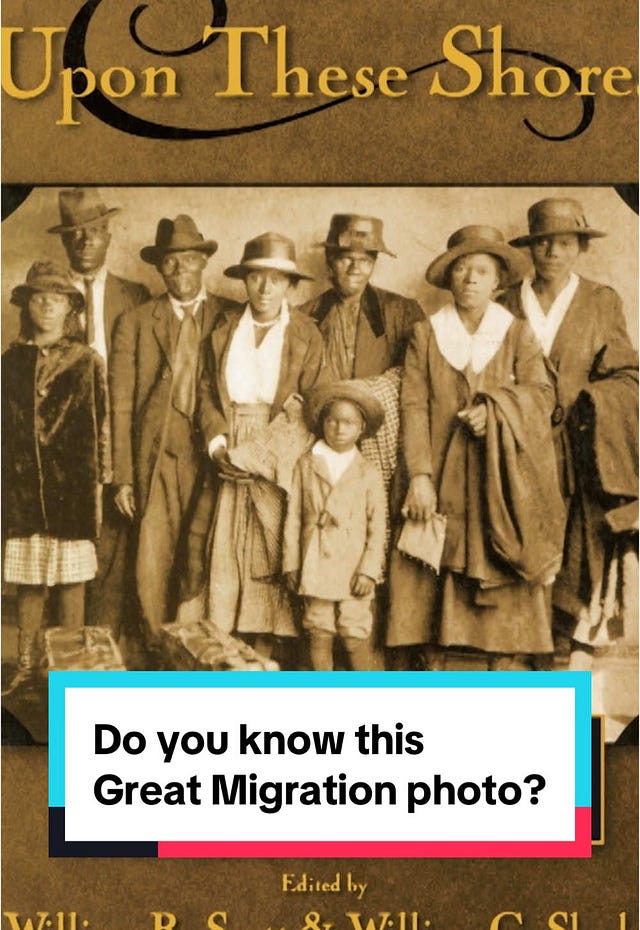

There’s an interesting phenomenon in Black History. When history books reflect on the experiences and milestones of Black people in America, they usually detail the trauma or highlight the success. On the other hand, we do not often get to understand the humans behind these fantastic moments. Therefore, many of the stories we learn about feel like fairy tales about supernatural beings. Their experiences are far too peculiar for us to find them relatable.

And yes, Black history is full of stories about the fantastic things Black people did, but those Black people were human. Like most humans, if we take a second to learn about them, we realize we have more in common than we initially thought possible. Take the Arthur family, for example. Scott and Violet Arthur, the leaders of this family, were not incredibly wealthy, exceptional at sports, or even intellectually superior to those around them. There wasn’t anything extra special; they were a regular Black family.

After years of hard work, the Scott family built a stable life in Paris, Texas; that life didn’t give them the luxuries of the ultra-rich, but it did afford them housing, food on the table, and the respect of their neighbors. The Arthurs were a humble family; they took care of their land, sent the right portions of food and rations to their landlord, and gave the church tithe. When the great migration began to pick up speed, they had no intention of leaving the only home they ever knew. They would spend the rest of their lives in Texas if it were up to them. Unfortunately, this wasn’t a decision that was under their control. Their simple life would soon turn into a tragedy.

Let’s fast forward a bit; on August 30th, 1920, the Arthur family finally made it to Chicago after an exhausting train ride from Paris, Texas. What brought Scott, Violet, and their family to Chicago wasn’t a search for jobs or better housing; it was white supremacy and terrorism. After facing constant harassment from their landlord, the family decided it was time to leave before things escalated to the point of no return. Unfortunately, they were too late. According to accounts from the Chicago Defender, “Against the custom, Hodges (Their Landlord), 61, had wanted the Arthurs to work all day every Saturday. When they refused to continue, Hodges ransacked the Arthurs’ home while his son, William, 34, held a gun on the family. Days later, as the Arthurs loaded their truck to leave, the Hodges returned and began throwing the furniture off the truck.”

Here’s the thing about this incident: the Arthurs were a well-respected family in their small community, even more so after World War 1. When their sons Erving and Herman Arthur returned from their service, they were treated like heroes by the small Black community. They didn't just feel like this reception was earned; they also believed that by fighting for their country, they had a right to be treated as equally as any white man. Maybe that’s what drove them to stand up to their landlord and set the family on a path that would impact history. The brothers hadn't responded during the first incident with Mr. Hodges; this time was different. After trying to escape, the brothers felt they had no choice but to respond, and according to accounts from witnesses there, “one of the Arthur brothers went inside, got a shotgun, and killed the landlord.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The Arthurs understood the ramifications of these actions and fled to Oklahoma; a Black man named Eric Adams Pitt McGrew revealed their location to the authorities. They were taken back to Texas and put in a holding cell to wait for a trial. As one would expect, that didn’t last long, and soon, an angry mob arrived demanding that the brothers be released to them. The “authorities” complied. The brothers were taken from the jail, brought to the fairgrounds, and then burned alive for all to see. While this was happening, the mother and daughters were taken into “protective custody,” where they were beaten and raped by 20 men.

The burned corpse of the brothers was then attached to a car and dragged down the street for all to see. The remaining family, after being released from police custody, hid in the woods, where they almost starved until they were able to make their escape to Chicago. Today, there are three descendants from that family. The American experience is littered with horror stories like this; it’s no wonder the current regime doesn’t want us to discuss it. But the wonderful thing about history is that it allows you to see the present and, if you’re lucky enough, sometimes the future.

Forty years after the Arthurs made it to Chicago, a woman named Lela Mae William and her nine children rode a bus from Little Rock, Arkansas, to Hyannis, Massachusetts, the home of the Kennedys. As far as we know, Lela had no intention of ever leaving Little Rock but made the hard choice to move after being promised a good-paying job, guaranteed housing, and a “presidential welcome.” Try to put yourself in Lela’s shoes; she packed up everything and took her children across the country for a better life. I can only imagine her hope and excitement while sitting on that long bus ride and her joy while telling her kids that they were onto something bigger and better.

The move would be challenging, but their destination would offer so much more than their previous circumstances could. After three days of riding on a bus without air conditioning, Lela Mae stepped onto the streets of Massachusetts in her Sunday best. With a heart full of optimism she expected to be greeted by President Kennedy and his family; instead she was met with a horde of reporters and a bunch of broken promises.

Lela Mae, like hundreds of other southern Black Americans, had been lied to by racist white southerners who orchestrated “reverse freedom rides”, an effort that sent Black people to northern states to show that North whites didn’t want them there either. White southerners believed that sending the poorest Black people they could find to Northern states would add pressure to cities already struggling with limited resources and low housing stock. This type of pressure would eventually prove that white northerners were hypocrites when they, too, demanded that Black people leave. The story of Reverse Freedom Rides and the backlash against migrants don’t get much attention today, and it should, maybe if more of us understood what happened in the past, we wouldn’t be so silent as much of our present-day is replicating those same sins.

During Biden’s four years in office, Republican Governors sent thousands of migrants to northern states with the promise that they would receive housing, work, and a second chance. In Texas alone, the Right-Wing Governor has used over 100 million dollars of tax-paying money to bus migrants to Blue cities and states like New York, Chicago, and Massachusetts. The influx of people to these states and cities has been hard to manage. Still, since Republicans picked up this strategy, the support for immigration reform and undocumented people has taken a significant hit. That has culminated in the election of Donald Trump. To be clear, Trump wasn’t elected solely because of an erosion of support for immigration reform, but it was one of the issues that registered high on the voters' list.

Since returning to office, Trump has used this sentiment to unleash a deportation plan that isn’t just wide-ranging; it is profoundly callous and harmful. We are only one month into his second term, and his administration, as of February 3rd, 2025, has deported at least 5600 people and is pushing to have Ice arresting and deporting at least 1400 people per day. On top of this, the administration is revoking temporary protected status from more than 300,000 Venezuelans currently living in the U.S. The final piece to his deportation program is an executive order that Trump signed, which would allow for the U.S government to hold up to 30,000 people facing deportation in Guantanamo Bay. Some people believe this type of action is necessary, they have forgotten we’re talking about people who are just like them.

My father came to this country in his 20s after a friend told him this was the “Land of Opportunity.” He left his home in the commonwealth of Dominica, landed in New York, expecting the streets to be paved with gold. He was greeted with blistering cold weather and back-breaking work. After years of struggling, he was able to make a life for himself, but like the Arthurs, if he could have stayed home and gotten these same opportunities, he would have never left. The Arthurs fled to Chicago for safety, my father came to New York for the opportunity, and Lela Mae left Arkansas for the chance at a better life. These are not “Black experiences” they are human experiences.

People migrating to the U.S. from Venezuela, Mexico, Senegal, Haiti, and other parts of the world aren’t here because they want to; they’re here because they have to. They’re here for the chance to raise their families with safety and dignity; they’re here because their countries can no longer provide these things. In some cases, our government is at fault for the instability in their homes. The gap between those who have, and those who don’t is bigger than ever before, the cost of living has skyrocketed and will continue to do so, and while this is happening, fewer people feel safer in the communities they live in. These conditions make it harder to think about others, but we can’t let our struggles make us heartless. History teaches us many things; in this case, hopefully, it shows you how much of what we are experiencing is a remixed version of white supremacist tactics, but that’s not all we should take from this lesson.

More than anything, history reminds us that no matter who we are, our skin color, or our political ideology, we are all human and connected. We don’t need to repeat the mistakes of our ancestors, especially when we have more tools than we could ever imagine. Things are scary right now, but we can rise above the fear; let’s not spin down another cycle of doom.

For the life of me, I can not understand the depths of hatred and violence of many of my white brothers and sisters. I grew up with racists and what I can see now is how consumed they were by fear of “others”. I’ve come to believe that was a projection of their own feelings of self loathing and violent rage. And I do clearly remember how the culture fed me a constant diet of white supremacy. These stories are important. They are heartbreaking.

There is nothing new under the sun...nothing!