Jimi’s Hands Worked

Within the scope of the fight for basic, essential civil rights, we sometimes overlook the ‘simpler’ things lost and how being different is defiance in itself.

Welcome to Let’s Not Be Trash, this post is a part of a larger series titled, “Our Ancestor’s Hands Do Work” It’s a collection of essays and conversations that highlight leaders, ideas, movements, and moments from the rich history of Blackness. You can keep track of all of the essays here.

If you’re new, please consider subscribing, if you’re already on the list and have a few coins, consider upgrading to a paid subscriber. If you have commitment issues but want to contribute, you can buy me a coffee.

If you like my substack and want to discover other great writers, check out this directory fromMarc Typo, called TheCook-Out.

This series is called “Our Ancestors’ Hands do Work” to dispel the extremely insulting narrative that previous generations were ‘passive’ in their rebellion against injustice. Now, in many contexts, this means physical resistance through disobedience and self-defense, which was absolutely necessary, but for this piece, I wanted to focus on another aspect of hands undeniably working—to create.

Jimi Hendrix’s passion for music was never going to leave. No matter how it looked to outsiders of his Experience, no matter what got in his way. Even when he was essentially forced to join the army to avoid jail time for petty theft, he had his guitar shipped to him while stationed. This was his journey. Legal channels and the system was just part of his tuning.

Ultimately, Jimi, a paratrooper for the army, was honorably discharged. After leaving the service and starting a band, his dream was launched, and he never looked back. Didn’t matter that in the early 60s his rights were unequal in the eyes of the law. Didn’t matter that nearly all rock guitarists and singers were white. He had the art. He was going to frame it his way.

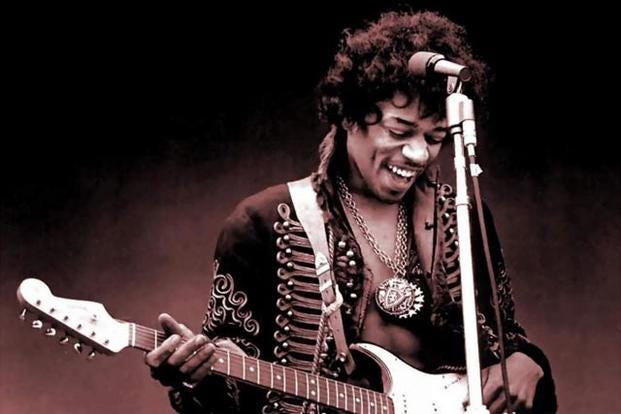

But, at the time, Jimi was unfairly characterized as not caring enough about the civil rights, his blackness, the struggle. He was a black man in a genre, while based on black music, in the public stardom at least, was almost entirely white. Even among the craft of being a guitarist he stood out. He played with flare. He played with his teeth. He wouldn’t contain his fire.

This in itself is resistance. He didn’t feel he needed to be any less flamboyant because he was a black man in a “white man’s” genre. He didn’t feel the need to adhere to any style of playing that was in line with anyone or any time. Like the another black man to follow who would become an all time great guitarist, Tom Morello, Jimi wanted to reconstruct the entire landscape of what a guitar can do. He created sounds that guitars just weren’t expect to make.

Jimi may not have always been the most vocal or choose to align with other organizations for liberation. But Jimi himself was liberation—on the stage. He is a black man liberated to play any music he wants, how he wants. He showed kids in America of all colors that difference is defiance. And it sounds damn good.

Also, Jimi did use music in pointed ways to make statements. His rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” during Woodstock was a protest in itself. As writer John Blake for CNN puts it to poignant effect:

[Jimi’s] classic take on “The Star Spangled Banner” at Woodstock was noted for its sonic impact: Hendrix summoned the sounds of falling rockets and bursting bombs from his guitar. Yet others heard something more, a black man’s protest. Hendrix played the song at the height of the Vietnam War, where black soldiers were dying in high numbers. He reportedly refused the pleading of his white business manager to forgo performing the anthem for fear of provoking a riot.

Hendrix’s interpretation of the national anthem was a protest on par with King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” says Wells, the English professor. Hendrix took a founding American document and reminded Americans how far they had strayed from their values.

“It was like Hendrix was saying, ‘This is my country. This is my national anthem,’ ” Wells says. ” ‘Now look at what I’m going to do with it.’

There are many ways for hands to work. Our ancestors of revolution for equitable existence demonstrated the full spectrum. The hands that picked themselves up from the force of billyclubs and firehoses of brutality, the hands that held onto a water fountain, bus seats, or dining stool in a white’s only place; the ones that literally smoked in the face of racism.

(Apparently, her name is Louisa Jenkins, so I want to put respect on it).

But hands can create art. And hands of creativity are indeed hands of defiance. Let’s not downplay those who shined black joy in the face of supremacist hatred.

It’s a devastating thought, but it’s important we ask ourselves from time to time: How many did we lose?

How many Jimis did we lose? How many beautiful songs will we never hear?

The fight for baseline humanity for black people sometimes overlooks the simple human need for magic. The magic of creation from sheer will and spirit alone; and thus, in such an oppressive environment—the creation that never was. The artistic, soul-draining battles injustice causes. The people who had to work just to be able to work, who, given the same freedoms of everyone else, may have composed symphonies. The people whose concerts died with them.

Jimi only lived 27 years, but his life was a symphony of his own chords. And he died proud of their melody. We should celebrate the tune of his black history. We should amplify every other tune that sang through the distortion of those trying to steal black joy during a time it was seen as contraband.

I was 15 years old when I decided to play the guitar, and I am still a guitar player to this day. And Jimi Hendrix is one of those folks I looked up to to remind me that I belong in the world of black guitarist/rock music. I remember reading a biography of him that was put together through quotes of folks who knew him telling his story and interviews…as I read this piece I was reminded of that and my past, a Black girl reaching for models.

This post honors him so well. Thank you for writing!