From Private Equity to Prostitution: How Men Extract Value Everywhere <3

Men follow the same playbook in their investing strategies as they do when the solicit sex

This is a guest post written by chickenpotpielover69 You can find more of her writing at the link below.

My relationship to and understanding of power, especially in relation to men, shifted almost immediately after I escaped sex work and started working as an associate a tech-focused private equity firm. I was working for and negotiating with the same types of men I used to meet on Seeking Arrangements—the same men themselves—but now I was navigating the power I could wield with my mind instead of my body.

Managing partners in private equity—mostly men—execute investment strategies that aren’t all that different from how they exploit women.

Private equity firms typically invest in more established businesses—often acquiring controlling ownership—with the goal of restructuring, scaling, or “optimizing” them before selling at a profit.

Private equity, simply put, most commonly involves an investment firm buying a majority stake—or the entirety—of a company.

These companies are typically the kind that could be described as boring, stable, and predictable: cash cows for private equity firms. The firms invest in these businesses, “optimize” them, and sell them at a higher price than they paid.

Let’s look at a hyperbolic scenario of how private equity works—think about a man, for example, rather than a company. This man has fewer than a few hundred Instagram followers. Maybe he doesn’t have Instagram at all. He wears khakis, but not in the cool, vintage, baggy, ironic way—more in the divorced dad who would go to Chili’s way. He doesn’t really have a personality of his own outside of things he’s learned on Reddit, and most of his jokes are recycled from women. But for some reason, you see potential in him (maybe it’s the fact he has no Instagram presence, whatever your prerogative is).

So you start investing in him. You upgrade his wardrobe, his sense of style, his humor—really, his entire aura. He starts posting cool film photos of himself that you took on your film camera to his Instagram. Before you, this guy couldn’t even get a date on Hinge—brotha wasn’t even getting likes. Now he’s posting up on Raya, pulling baddies who used to soft-launch B-list rappers. And then one day, poof—he’s gone. Some other girl snatched him up at full price, and she thinks she got a steal, but you know better.

Here’s how private equity actually works, in plain English:

Private equity firms raise massive sums of money from big investors—pension funds, endowments, rich people—and use it, plus a lot of borrowed money, to buy companies. Once they own a business, they set about “improving operations.” Translation: make it more profitable. After three to seven years, they sell it for more than they paid.

Here’s the kicker: the debt used to buy the company doesn’t sit with the PE firm—it gets loaded onto the company itself. That means the business has to generate enough cash not just to pay the debt, but also to deliver a return to investors. The pressure to extract value is baked in.

Say a firm buys a veterinary clinic chain at ten times earnings, planning to sell at fifteen. Where does that extra value come from? Usually it comes from raising prices, cutting staff, slashing services that don’t generate revenue, consolidating operations, squeezing suppliers. Value is extracted, piece by piece, from the people and systems already in place.

This is why PE is obsessed with certain industries: fragmented markets, steady demand, pricing power. Healthcare, housing, childcare—things people can’t easily delay or shop around for. In other words, the model works best when there’s cash you can reliably take, with minimal resistance.

Private equity, in practice, is a system designed to extract. And once you understand that, it becomes impossible not to see the pattern repeating itself elsewhere—in the men I used to meet, in the deals they make, in the way they assume they have the right to take what isn’t theirs.

Men follow the same playbook in their investing strategies as they do when they solicit sex: buy it for as little as they can, extract as much value as possible, and shift the debt—the burden of the transaction—onto someone else. In private equity, that debt sits on the company’s balance sheet. In sex, it settles into the woman’s body.

An LBO model is, at its core, a projection of how much you can take. You input revenue growth, margin expansion, cost savings, debt tranches, interest rates. You flex assumptions until the returns look attractive enough—until the internal rate of return crosses whatever arbitrary hurdle makes the deal “worth it.” The entire spreadsheet is built around one central question: if we buy this for X, how much can we extract before we sell?

You sensitize downside cases. You stress-test cash flow. You calculate how much debt the company can “handle.” Handle is a polite word. It really means: how much pressure can this thing withstand before it cracks?

It felt eerily familiar.

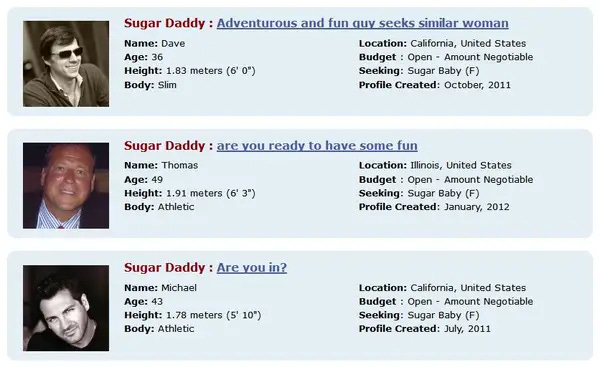

On Seeking Arrangements, men ran their own informal models. What’s her allowance expectation? How often will she meet? What are the boundaries? How far can I push them?

They, too, were underwriting risk. They wanted maximum access with minimum investment. They wanted predictable availability, steady performance, limited downside.

In both cases, the calculus centers on capacity. How much can this company bear? How much can this woman tolerate? How much debt can be layered on before something gives? How much of her time, her body, her emotional labor can be extracted before the returns diminish?

The spreadsheet never shows what erodes.

In companies, it’s morale, service quality, institutional memory—the soft things that don’t fit neatly into EBITDA. In women, it’s harder to quantify but no less real: boundaries, desire, a sense of self that isn’t constantly being priced and negotiated. You can lever both aggressively and still make the numbers work, at least for a while. The model will tell you it’s sustainable. The human cost doesn’t get a line item.

And that was the strangest part of sitting in those boardrooms. I understood the logic. I could build the model myself. I could calculate the returns. I could speak their language fluently. But I also knew what it felt like to be on the other side of a transaction structured for someone else’s gain. Transactions of entirely different natures, structured by the same men.

In one room, they called it leverage. In another, they called it chemistry. In both, it was a capital meeting asset. They brought the money. I—or the company—brought the thing to be used.

I would sit there while they debated how much debt a business could reasonably “support.” That was the word. Support. As if the company were volunteering to carry it. As if balance sheets had consent. They spoke casually about pressure—how much was optimal, how much created discipline, how much could be layered on before performance started to slip.

I had once been evaluated the same way. How much time could I give? How flexible were my boundaries? My legs? What was the minimum investment required for maximum access? They called that negotiation. They called that mutually beneficial.

In Excel, you toggle assumptions until the returns look attractive. Increase leverage. Trim costs. Push margins. You build in a downside case, of course—no one wants the asset collapsing entirely. The goal isn’t destruction. It’s controlled extraction. Just enough pressure to maximize output without triggering failure.

That logic felt familiar in my bones.

Because I, too, had learned to calibrate myself. How much of my body could I detach from? How much enthusiasm could I manufacture? How much debt—emotional, physical, psychological—could I carry in exchange for rent money? The arrangement worked as long as I remained functional. As long as I didn’t crack.

The spreadsheet never models erosion. It doesn’t account for morale or dignity or the slow hollowing that happens when something is valued only for its yield. It assumes stability as long as the cash flows.

Sitting in those boardrooms, speaking their language fluently, I understood the math. I could calculate IRRs. I could defend leverage ratios. I could argue for operational efficiencies.

But I also knew what it felt like to be the line item absorbing the pressure.

Congratulations, you made it to the end! Did you enjoy this post? Great, leave a comment and then subscribe to chickenpotpielover69 newsletter for more post like this.

I coached MBA students at a top five business school but I didn't work directly with students interested in finance but I knew them enough to completely concur with your assessment. All those entangled with Esptein, the type of men they are is not hard to explain at all.

The parallel between high-risk investment behavior and sexual entitlement makes total sense when you think about how both stem from the same fundamental belief that rules don't really apply to them. What's wild is how this mentality gets reinforced in elite circles where the financial upside of bending rules has historically outweighed any real consequences. Makes you wonder how many other domains this same psychological pattern shows up in beyond just finance and sexual misconduct.